Advanced Therapies

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is one of the main approaches in psychotherapy. The principle of CBT is identifying a negative thought about a specific situation and then changing this negative thought to a more realistic and positive thought. The general framework of CBT is known as the A-B-C model (Activating event – Beliefs or automatic thoughts – Consequences or reactions).

One of the most important procedures in CBT is the identification of a belief or automatic thought. An automatic thought is one that arises spontaneously in response to a specific situation.

Cognitive models tell us that cognition comprises automatic thoughts (spontaneously in response to a situation), intermediate thoughts (like rules or assumptions), and core beliefs (developed in childhood and more fundamental).

Patients have a tendency to view their automatic thoughts as truth because automatic thoughts are, literally, automatic, they are considered to “pop up” in one’s mind. In CBT, the clinician and patient work together to frame the automatic negative thought as a hypothesis that may or may not be true. In a process called empirical collaboration, the clinician and patient evaluate the patient’s negative thoughts together.

After evaluating the negative automatic thoughts, the clinician offers more positive and realistic thoughts to replace them. This procedure (identifying automatic thoughts and evaluating their validity) should be performed not only during counseling sessions but also between sessions. The patient’s active participation is essential, which is why homework is important (Jun, H.J., 2013).

Internet-based CBT

CBT is constantly evolving in part to improve its’ effectiveness and accessibility. Internet-based CBT (ICBT) provides a possible solution to overcome many of the barriers to accessing face-to-face therapy. Therapists can provide support to patients who are accessing Internet-based therapy by telephone, e-mail or now by a mobile App.

Researchers have explored the possibility of using the Internet to deliver CBT. Internet-based training (IBT) programs that include supervision may be a scalable and effective method of disseminating CBT into routine clinical practice, particularly for populations without ready access to more-traditional “live” methods of training.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy.

Hayes (2004) described three successive waves in behavior therapy, each characterized by “dominant assumptions, methods and goals”: traditional behavior therapy, cognitive therapy and therapies based on mindfulness meditation and acceptance.

In the first generation of behavior therapy it was possible to keep both commitments because traditional behavior therapists drew on a large set of basic principles drawn from the basic behavioral laboratories. Even in the earliest days, however, authors of behavioral principles texts realized that this base needed to expand beyond operant and classical principles to include those focused on human cognitive processes (Bandura, 1969). Clinicians realized that as well, and this realization was at the core of the second generation of traditional cognitive therapy and cognitive behavior therapy.

Hayes (2006) calls third-generation therapies those that include processes of mindfulness and acceptance and commitment in their components. ACT is linked to a comprehensive active basic research program on the nature of human language and cognition (Relational Frame Theory), echoing back to an earlier era of behavior therapy in which clinical treatments were consciously based on basic behavioral principles (Hayes, 2004). According to Relational Frame Theory (RFT), the unique strength of the human mind lies with its ability to derive countless arbitrary connections among stimuli.

It has been seen as the RFT allows to incorporate the language, the thought and the cognition to the behavioral therapy, incorporating marginal concepts in cognitive behavioral therapy as the concept of self and mindfulness.

The therapeutic process in ACT is directly based on the perspective that the experience of psychological pain is unavoidable and that the use of experiential avoidance and similar coping mechanisms to deal with this pain, though understandable, often increases suffering.

ACT and CBT

CBT and ACT both encourage adaptive emotion regulation strategies but target different stages of the generative emotion process: CBT promotes adaptive antecedent-focused emotion regulation strategies, whereas acceptance strategies of ACT counteract maladaptive response-focused emotion regulation strategies, such as suppression.

Although there are fundamental differences in the philosophical foundation, ACT techniques are fully compatible with CBT and may lead to improved interventions for some disorders.

It is possible to combine traditional CBT with third wave approaches by using psychoeducation and cognitive restructuring in the beginning phases of therapy in order to establish thought bias and to then encourage acceptance of internal experiences as well as exposure to feared stimuli rather than to continue to use cognitive restructuring techniques.

Epigenetics.

Obesity results from interactions between environmental and genetic factors. Despite a relatively high heritability of common, non-syndromic obesity (40–70%), the search for genetic variants contributing to susceptibility has been a challenging task. Genome Wide Association (GWA) studies have dramatically changed the pace of detection of common genetic susceptibility variants. To date, more than 40 genetic variants have been associated with obesity and fat distribution. However, since these variants do not fully explain the heritability of obesity, other forms of variation, such as epigenetics marks, must be considered.

Until 2006, the main approaches used to track down common variants influencing obesity, involved either hypothesis-free genome-wide linkage mapping in families with multiple obese subjects or association studies within ‘candidate’ genes using case–control samples or parent–offspring trios. The former suffered from being underpowered for any sensible susceptibility models, as linkage is best placed to detect variants with high penetrance. As far as we can tell, common variants with high penetrance do not contribute substantially to risk of common forms of obesity and few, if any, robust signals have emerged from such efforts. The latter candidate-gene association approach has historically been compromised by difficulties in selecting credible candidates. Selection was typically based on hypotheses about biological mechanisms putatively involved in obesity pathogenesis but, as the function of much of the genome is poorly characterized, it remains almost impossible to make fully informed decisions. In addition, all too often these candidate-gene studies were conducted in sample sets far too small to offer confident detection of variants with the range of effect sizes that are now known to be realistic. With hindsight, it is easy to appreciate why these approaches yielded few examples of genuine obesity–susceptibility variants.

Consequently, over the last two decades, efforts in identifying and replicating genetic variants predisposing individuals to common forms of obesity were largely characterized by slow progress and limited success, in sharp contrast to the successful gene identification in monogenic and syndromic forms of obesity (Rankinen T., 2006). The most recent edition of the “Human Obesity Gene Map” gives an excellent overview of this; it lists 11 single gene mutations, 50 loci related to Mendelian syndromes relevant to human obesity, 244 knockout or transgenic animal models and 127 candidate genes, of which slightly less than 20% are replicated by 5 or more studies (Rankinen T., 2006). A total of 253 quantitative trait loci (QTL), for different obesity-related phenotypes, have been reported from 61 genome-wide linkage scans and of these, only ∼20% are supported by more than one study (Rankinen T., 2006).

Epigenetics and ACT

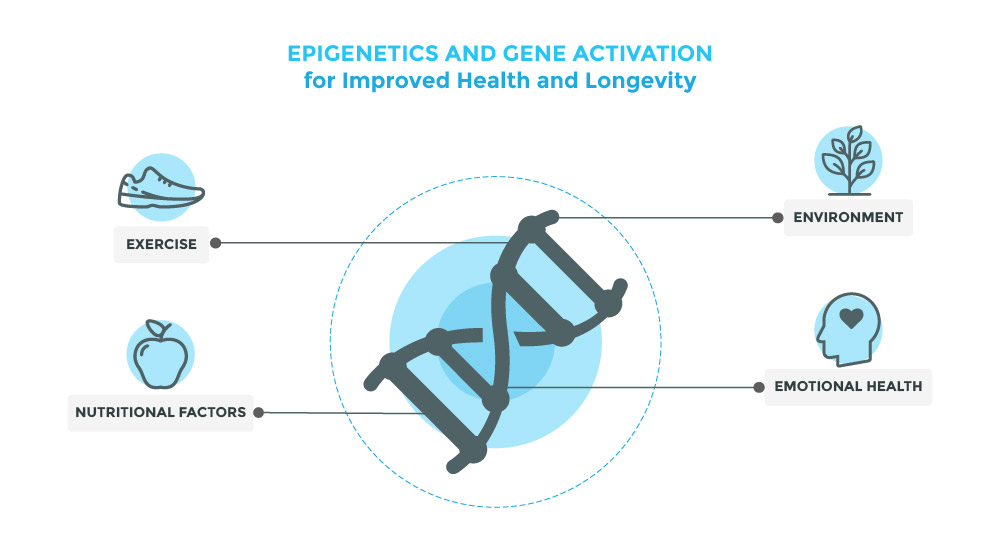

The concept of “lifestyle” includes different factors such as nutrition, behavior, stress, physical activity, working habits, smoking and alcohol consumption. Increasing evidence shows that environmental and lifestyle factors may influence epigenetic mechanisms, such as DNA methylation, histone acetylation and microRNA expression.

Several lifestyle factors have been identified that might modify epigenetic patterns, such as diet, obesity, physical activity, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, environmental pollutants, psychological stress, and working on night shifts.

Most studies conducted so far have been centered on DNA methylation, whereas only a few investigations have studied lifestyle factors in relation to histone modifications and miRNAs.